Written and directed by Aki Kaurismaki

Cinematography Timo Salminen

Starring Andre Wilms, Kati Outinen, Jean Pere Daroussin, Blondin Miguel and Pierre Etaix

It is not very often that a film labelled "art house" features a happy ending and gets away with it. But (Spoiler Alert!) Aki Kaurismaki attempts exactly that in this comic drama set in the French coastal town from which the film derives its title. And the way the film has been received at major festivals, it could very well seem that the director's courage has paid off.

Centred on an aging shoeshiner Marcel Marx (Andre Wilms) and his efforts to protect and rescue a young African stowaway Idrissa (Blondin Miguel) by dispatching him off to his mother in London, Le Havre could, in lesser hands, turn into an escape thriller in the Hollywood tradition. But Kaurismaki has the entire action played in deadpan, infusing the film with a sense of detachment that only adds to its charm. Yet the film does not fail in winning our empathy for Marcel, Idrissa and Marcel's ailing wife Arletty (Kati Outinen) hospitalised early on in the film with an illness for which the doctor (Pierre Etaix) says there is little hope.

Marcel's efforts at sending Idrissa to London puts him at odds with inspector Monet (Jean Pere Daroussin), whose efforts he must evade to accomplish the task he has set out for. An even greater challenge is raising the money for the journey. But Marcel is determined in his resolve to help the boy.

The thing that is striking about Le Havre is its imagery. In both the photography and the mise-en-scene, Kaurismaki's style is deliberately old-fashioned. Not only is the staging resourcefully simple, with minimal camera movement, but the film, so it seems to me, has completely stayed clear of any digital manipulation, completely keeping its faith in the photo-chemical process. That takes some courage, especially these days.

Watching the film, one is initially confused as to the period in which it is set. While the initial scenes, with Rock 'n Roll music in the background may have you believe that the film is set somewhere in the 70s, a reference to the Al-Qaeda would confirm that the film is set somewhere in the post 9/11 world. Though the film does not make any explicit political statement, it is hard to miss the political undercurrent that runs through it.

Le Havre, in that sense, is Kaurismaki's way of keeping faith in humanity even in our deeply cynical times, that there is room for compassion even in turbulent times. To condense the review in a nutshell, Le Havre brings together the humanism and politics of Chaplin and the deadpan humour of Keaton.

Written and Directed by Charles Chaplin

Music by Charles Chaplin

Cinematography Roland Totheroh

Starring Charles Chaplin and Paulette Goddard

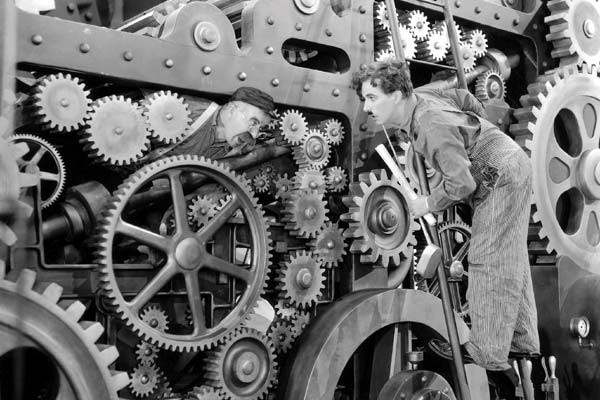

Charlie Chaplin's depression-era masterpiece Modern Times was to represent a significant change in the icon's body of work from this point on. Not only was it his last silent picture (not entirely silent, though, for reasons which we will come to later) and the last vehicle for his character of the Tramp (though a variation of the character could be seen in The Great Dictator), but every subsequent film of his- with the possible exception of Limelight -would have overt political backdrops.

With his overnight rise to international stardom in the late 1910s and subsequent entry into artistic and political circles, Chaplin began to become increasingly politically aware, and it was inevitable that his "political awakening" would be reflected in his work. His interest in world events led the actor-filmmaker to seek meetings with Mahatma Gandhi and Winston Churchill among many others. Gandhi and his views on industrialisation especially seemed to have made a strong impression on him. But it was not simply the perils of industrialised labour that the film would come to address. The devastation caused by the Great Depression of the 30s, which he witnessed on his trip and back in America, would also find their way into the film.

Despite its grim premise, Modern Times is actually a light-hearted take on the social realities of the time. While general reviews of the time could see nothing beyond the humour, other critics were miffed with the film's refusal to talk when the world was held in sway by talking pictures, its eschewing of plot, and its simple visual style, which seemed dated to many. More highbrow critics disdained its political ambiguity.

There is no doubt that the film does veer in tone- the futuristic vision in the initial factory sequences giving way to a more contemporary milieu in the rest of the film, Modern Times is rather uneven in tone. But the brilliance of these sequences more than compensates for this minor flaw.

The opening montage- A shot of a herd of sheep dissolving into one of factory workers and a shot of a large factory, is very evident of Chaplin's political leanings. What follows is a series of sketches that begin with the Tramp tightening nuts in a factory that manufactures God-knows-what, until he himself goes nuts over the increasing demands thrust upon him and other workers. Joined by a gamine (Paulette Goddard, his third wife), they fight it out against a world that is becoming increasingly mechanised and profit-driven, to assert their individuality. While they find little success, they are determined to keep fighting.

As with most of Chaplin's work, the things that stick to your mind are the set-pieces- the Tramp being used as guinea pig on a feeding machine that feeds the workers while at work so that the lunch hour could be eliminated, the home that the Tramp and Gamine dream up for themselves, the ballet on roller skates, the Tramp's routines as waiter and so on. While most of the gags aren't fresh in themselves (He does refine some of his old routines from the shorts made for Mutual two decades earlier), he improves upon them, incorporating his own physical dexterity and improved sense of timing, that they blend seamlessly into the narrative.

The characterisation in Modern Times is worth a mention. Apart from the tramp and the gamine, very few characters have any significant screen time. Even the credits mention only two characters, that of the Tramp and the Gamine, the others simply mentioned as supporting players. Their significance is reduced to that of any other prop, simply entering and leaving after their role in the story is finished. Could this be a hint that the world is increasingly peopled by automatons?

While the opening montage was enough to brand Chaplin as a leftist in an America that treats any leftwing tendency with utmost derision, another sequence that makes a more explicit reference to communist paranoia in the States would forever brand him as a Red in the eyes of Americans. This, perhaps one of the most brilliantly executed set pieces in the film, shows Charlie picking up a red flag dropped from a truck and walking towards it, only to be nabbed by the police who suspect him to be a communist leader. Using no words, and in no more than five shots, Chaplin succeeds in driving home the message. Watching this sequence, one wonders what the pundits who brushed aside Chaplin as "uncinematic", were actually thinking of.

Another remarkable facet of the film is its sophisticated use of sound. True, Chaplin was averse to talk, but he was not averse to the possibilities that sound offered the filmmaker. In his previous release, City Lights, he took the plunge into the sound film by composing a score and adding a few sound effects. But he took his experiments even further here. The only "sounds" you hear in Modern Times are the sounds of machines, of objects. The human voice is otherwise silenced, heard only through a machine like a television screen, radio, or a record. The only person who finds his voice in the film is the Tramp, who breaks into song towards the end, but which is of no particular language, for he is bereft of linguistic barriers. One particular sequence, involving the Tramp and a woman having a cup of tea, is particularly notable, anticipating the work of Jacques Tati.

Modern Times would find more acceptance in the post-WW2 era, and its influence could be seen in works like George Orwell's 1984, with its Big Brother and telescreen clearly reminding us of Chaplin's film. While the film could be considered Chaplin's most formally inventive work, it endures because of the way it resonates with our own times.

Produced and Directed by Jacques Tati

Written by Jacques Tati, Jacques Lagrange and Jean L'Hote

Cinematography Jean Bourgonin

Editing Suzanne Baron

Starring Jacques Tati, Jean Pierre Zola, Adrienne Servantine, Alain Becourt

How do you study a film that is devoid of plot or detailed character analysis and yet is a classic?

Jacques Tati is perhaps the cinematic equivalent of Samuel Beckett, whose plays dispensed with the Aristotelian tradition of storytelling, which laid emphasis on plot and characterisation. Both Beckett and Tati dealt with the increasing isolation of the individual in the modern world.

As one of the major filmmakers during the post-war era, Tati, along with others like Antonioni, Bresson, Bergman and Godard, would be instrumental in changing the way films were read. His third feature film and his first in colour, Mon Oncle is essentially a tour-de-force of set pieces involving Mr. Hulot, Tati's trademark character, and his sister's son Gerard, who lives in an ultra-modern house and spends every evening after school with uncle Hulot. While Gerard and his mother are fond of Hulot, his father, an executive at a factory, is disdainful of him, largely due to his simplistic ways.

Hulot's sister tries every trick possible to get her brother into respectable society, like getting him a job at her husband's plant and finding a girlfriend for him, but they all simply fall flat. Hulot simply does not fit in "society proper"

Several of the film's set pieces revolve around the ultra-modern house Gerard and his parents stay in. It goes without saying that one of the prime concerns of the film is its lampooning of modernity. But that is not all there is to it. Tati also takes several digs at a society that prides itself on status and wealth.

Mon Oncle earns its praise mainly due to the way Tati gets his points across to the viewer. His use of colour to pit the old-fashioned world of Hulot to the modern, sterile world of his sister and her family, is simply extraordinary for its time. The dull greys of the modern settings, with the occasional intrusion of strong colours, is strongly contrasted with the warmer colours of Hulot's old-fashioned world.

Tati's disregard for convention can also be seen in his mise-en-scene. Close-ups and editing within a given scene are generally eschewed, opting to let the scene play out in distant, uninterrupted takes. He compensates for this relative rigidity in camera style by making extensive use of choreography, which makes the images a delight to watch.

Even more demonstrative of Tati's flouting of convention is his use of sound, and the soundtrack of Mon Oncle, as that of all of Tati's work, is one of the most meticulously designed in all of cinema. While there is little dialogue in the film, what dialogue there is is largely reduced to being just another sound effect. And yet the soundtrack adds so much to the spirit of the film that a great deal of the film's humour is lost if you switch off the sound, despite the fact that there is little dialogue in it.

There are several analogies that rise when mention is made about the Hulot character, mostly to the Tramp character of Chaplin. They are similar in that we see the same character in successive films (Unlike Keaton, who had different names in each of his films, but shared the same traits). Both characters are non-conformists who do not give a damn about the world. But while the Tramp is a yearning romantic, Hulot is not and does not care to be. His cool detachment is more like the Keaton type.

Tati's brand of film comedy clearly draws from the work of the great silent comics, and he is perhaps the last film artist to have taken their legacy forward. Sure is a pity that this legacy has not been taken forward.

.jpg)