Directed by Jean Renoir

Written by Jean Renoir and Charles Spaak

Starring Jean Gabin, Marcel Dalio, Pierre Fresnay and Erich von Stroheim

With Grand Illusion (La Grande Illusion in French), the international film scene had taken notice of a hitherto unknown film-making talent- Jean Renoir, son of the famous impressionist painter Pierre-August Renoir. Renoir had been making silent movies from the 1920s and tasted success in the early 30s. With Grand Illusion, he became an international celebrity and the film was a popular success worldwide. Released in 1937, two years before the outbreak of WWII, the film's anti-war stance made it all the more significant.

But Grand Illusion is not set in the trenches. The film begins with the French Lieutenant Marechal (Jean Gabin) who, along with Captain de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) are captured by the German forces in an air raid during World War One and shuttled between prisoner-of-war camps in between their efforts to escape. In between this cat-and-mouse game, we come across a range of characters like the Jewish merchant Rosenthal (Marcel Dalio) and the German aristocrat Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim), bonds are formed across religious and national borders, and hope is revived in the human spirit.

While the term "war film" generally brings to mind a film with loads of violence, action-packed sequences and a somber ambience, Renoir's war film replaces them with warm humour and compassion, that most essential of human qualities.

Two decades before Grand Illusion, Chaplin's Shoulder Arms (1918) dealt with life in the trenches during WWI, where he discarded his usual sentimental approach to present us with a darkly comic view of the war. But Renoir, having been in the war himself, knew all too well that humanity could exist even in the direst of situations, even across hostile countries, races and religions. This is exemplified in the close friendship that develops between Boeldieu and Rauffenstein, Marechal and Rosenthal, and in the way the escaped prisoners are tended to by a German widow.

Accustomed as we are to reports of prisoners undergoing brutal torture in war camps, the treatment of prisoners-of-war in Grand Illusion does strike us as something new. Not only are they treated more like human beings, you also get to see soldiers having a nice time off the battlefield. Whether this was a luxury offered only the "whites", I'm not sure of.

All that aside, Grand Illusion is one of those films that has everything going for it; a well-knit script with deft characterisation, a magnificent ensemble cast, beautiful background score and Jean Renoir, what more could you ask for?

One of the aspects of the film that remains striking today but was overlooked at the time is Renoir's mise-en-scene. In the first decade of the sound film, when cameras equipped for sync-sound recording were fairly bulky, and without the luxury of shooting in studios, Renoir manages to accomplish complex camera movements which, with their fluidity, remain baffling. But at a time when Soviet montage was hailed as the pinnacle of the art of cinema, the long takes of Renoir, Mizoguchi and Ophuls was underestimated. It was not until Citizen Kane and Andre Bazin's ruminations that the long take came into vogue.

I've seen very few of Renoir's work, but of the ones I've seen, Grand Illusion takes him closest to his idol Chaplin, in its seamless interweaving of humour and pathos, and in the faith it retains in the human spirit.

Written and Directed by Charles Chaplin

Music by Charles Chaplin

Cinematography Roland Totheroh

Starring Charles Chaplin and Paulette Goddard

Charlie Chaplin's depression-era masterpiece Modern Times was to represent a significant change in the icon's body of work from this point on. Not only was it his last silent picture (not entirely silent, though, for reasons which we will come to later) and the last vehicle for his character of the Tramp (though a variation of the character could be seen in The Great Dictator), but every subsequent film of his- with the possible exception of Limelight -would have overt political backdrops.

With his overnight rise to international stardom in the late 1910s and subsequent entry into artistic and political circles, Chaplin began to become increasingly politically aware, and it was inevitable that his "political awakening" would be reflected in his work. His interest in world events led the actor-filmmaker to seek meetings with Mahatma Gandhi and Winston Churchill among many others. Gandhi and his views on industrialisation especially seemed to have made a strong impression on him. But it was not simply the perils of industrialised labour that the film would come to address. The devastation caused by the Great Depression of the 30s, which he witnessed on his trip and back in America, would also find their way into the film.

Despite its grim premise, Modern Times is actually a light-hearted take on the social realities of the time. While general reviews of the time could see nothing beyond the humour, other critics were miffed with the film's refusal to talk when the world was held in sway by talking pictures, its eschewing of plot, and its simple visual style, which seemed dated to many. More highbrow critics disdained its political ambiguity.

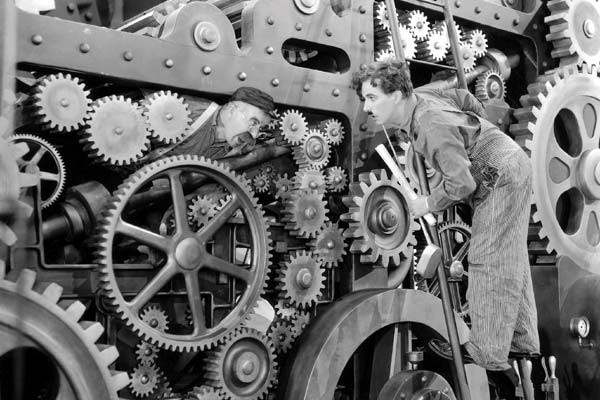

There is no doubt that the film does veer in tone- the futuristic vision in the initial factory sequences giving way to a more contemporary milieu in the rest of the film, Modern Times is rather uneven in tone. But the brilliance of these sequences more than compensates for this minor flaw.

The opening montage- A shot of a herd of sheep dissolving into one of factory workers and a shot of a large factory, is very evident of Chaplin's political leanings. What follows is a series of sketches that begin with the Tramp tightening nuts in a factory that manufactures God-knows-what, until he himself goes nuts over the increasing demands thrust upon him and other workers. Joined by a gamine (Paulette Goddard, his third wife), they fight it out against a world that is becoming increasingly mechanised and profit-driven, to assert their individuality. While they find little success, they are determined to keep fighting.

As with most of Chaplin's work, the things that stick to your mind are the set-pieces- the Tramp being used as guinea pig on a feeding machine that feeds the workers while at work so that the lunch hour could be eliminated, the home that the Tramp and Gamine dream up for themselves, the ballet on roller skates, the Tramp's routines as waiter and so on. While most of the gags aren't fresh in themselves (He does refine some of his old routines from the shorts made for Mutual two decades earlier), he improves upon them, incorporating his own physical dexterity and improved sense of timing, that they blend seamlessly into the narrative.

The characterisation in Modern Times is worth a mention. Apart from the tramp and the gamine, very few characters have any significant screen time. Even the credits mention only two characters, that of the Tramp and the Gamine, the others simply mentioned as supporting players. Their significance is reduced to that of any other prop, simply entering and leaving after their role in the story is finished. Could this be a hint that the world is increasingly peopled by automatons?

While the opening montage was enough to brand Chaplin as a leftist in an America that treats any leftwing tendency with utmost derision, another sequence that makes a more explicit reference to communist paranoia in the States would forever brand him as a Red in the eyes of Americans. This, perhaps one of the most brilliantly executed set pieces in the film, shows Charlie picking up a red flag dropped from a truck and walking towards it, only to be nabbed by the police who suspect him to be a communist leader. Using no words, and in no more than five shots, Chaplin succeeds in driving home the message. Watching this sequence, one wonders what the pundits who brushed aside Chaplin as "uncinematic", were actually thinking of.

Another remarkable facet of the film is its sophisticated use of sound. True, Chaplin was averse to talk, but he was not averse to the possibilities that sound offered the filmmaker. In his previous release, City Lights, he took the plunge into the sound film by composing a score and adding a few sound effects. But he took his experiments even further here. The only "sounds" you hear in Modern Times are the sounds of machines, of objects. The human voice is otherwise silenced, heard only through a machine like a television screen, radio, or a record. The only person who finds his voice in the film is the Tramp, who breaks into song towards the end, but which is of no particular language, for he is bereft of linguistic barriers. One particular sequence, involving the Tramp and a woman having a cup of tea, is particularly notable, anticipating the work of Jacques Tati.

Modern Times would find more acceptance in the post-WW2 era, and its influence could be seen in works like George Orwell's 1984, with its Big Brother and telescreen clearly reminding us of Chaplin's film. While the film could be considered Chaplin's most formally inventive work, it endures because of the way it resonates with our own times.

Directed by Vittorio De Sica

Written By Cesare Zavattini

Cinematography Carlo Montuori

Edited by Eraldo Da Roma

Music by Alessandro Ciccognini

Starring Lamberto Maggiorani and Enzo Staiola

Bicycle Thieves has become so iconic a film that it its reputation soars far higher than any other film made during what generally is called the "Italian Neo-realist" film movement. The neo-realist movement, which lasted roughly from the mid 40s to the early 50s, was a direct response to the devastation caused by World War II in Italy. The movement, which roughly began with Rossellini's Rome, Open City, is generally considered to have reached its artistic zenith with De Sica's 1948 masterpiece.

While umpteen films were made under the tag "neo-realist", only a handful of films have the worldwide acclaim as of now, and of the few that have, De Sica's film remains the most cherished by audiences. One could attribute this to the film's universality. While Rossellini's war trilogy was essentially Euro-centric, Bicycle Thieves, with its searingly simple premise of a man in search of his lost bicycle, made for a theme which anyone anywhere could relate to.

Like most art movements, what made neo-realism a landmark movement in the history of cinema was the distinctive aesthetic it introduced. No longer able to afford shooting within the confines of a studio or with bankable stars, filmmakers had to take their cameras out into the streets, filming with whatever light was available, and by using non-professional actors without make-up. As a result, cinema finally seemed to be shorn of all artifice, and viewers were confronted with bare reality presented to them, without the interference of any manipulation by the studio system.

There were films before the emergence of neo-realism that challenged conventional methods of filmmaking, like the Expressionist cinema of 1920s Germany, the Impressionist cinema in France of around the same period, and the Surrealist movement, but they occasionally used professional actors and studios. Films that veer close to the neo-realist aesthetic of that period would be Flaherty's Nanook of the North, which was shot on location without using professional actors, and Renoir's Toni in the 30s, which would similarly make use of non-actors. But these were individual efforts, and it hadn't yet been proved to the world that an entire cinema industry could make films that way. That would happen only after 1945. Films like Rossellini's War Trilogy and Bicycle Thieves proved that you could make a great film with only a camera and an inquisitive mind.

Yet it would be unfair to credit Bicycle Thieves as the product of one mind. For one, its plot was based loosely on a novella of the same name by Luigi Bartolini, which was turned into a screenplay by Cesare Zavattini, who wrote a great number of films during that period. Later, he would often fume at the fact that credit for the film's greatness went entirely to De Sica, and went so far as to claim that 90 percent of the film was his own creation. While you could credit the writer with his brilliant social observation in the film, since Zavattini himself claimed that he no involvement in the production, you could not overlook De Sica's contribution to the final work, especially in his mise-en-scene and the way he has evoked brilliant performances from a largely unknown cast of non-professional actors.

In its spare use of camera movements, montage and largely medium to long-shot framing, Bicycle Thieves has a stylistic austerity that is reminiscent of a Chaplin film. Even in its worldview, that of a dog-eat-dog world, it is not unlike the themes that pervade Chaplin's work. But it avoids the poetry, gracefulness, and the optimism of the Tramp, to present a more harsher, more fatalistic view of the world.

Upon release and international acclaim, Bicycle Thieves influenced several filmmaking countries of the time, notably in India, which had just emerged from colonial rule. The immediate influence of the film could be seen in films like Bimal Roy's Do Bigha Zamin and Raj Kapoor's Boot Polish, while a hitherto unknown Satyajit Ray borrowed the neo-realist aesthetic to scale poetic heights in his debut feature Pather Panchali.

Come May 3, 2013 and India's film industry will be celebrating the hundredth year of its birth, for it was on this day exactly a hundred years ago that Raja Harishchandra, supposedly the first Indian film made by the first Indian filmmaker Dadasaheb Phalke, hit theatre screens. In a country known for its lackluster approach to film preservation (bar the efforts of PK Nair, founder of the National Film Archive of India, on whom a documentary, Celluloid Man was recently made, which I have written about here), the fact that we have got the date on which the film was released right is indeed remarkable. But is Raja Harishchandra really India's first film?

A little more probing would reveal that there have been films made in the country before Phalke's feature debut. Shortly after the Lumiere brothers screened their "actualities" in Bombay (As Mumbai was officially called then) in the late 1890s, a certain Harishchandra Sakharam Bhatwadekar, or Save Dada, a portrait photographer, made a series of factual films a la the Lumiere Brothers in India, the first of which was a wrestling match between two well known wrestlers of the time, in 1899. He even filmed perhaps India's first newsreel, the arrival of RP Paranjpe, a successful mathematician, from Cambridge in 1901.

In fact, the non-fiction cinema seemed to have been active in India well before Phalke made his entry. By the first decade of the 20th century, cinemas were already established in major cities of the country like Calcutta, Madras and Bombay (though it could be assumed that these theatres screened largely foreign films, like those of George Melies and Edwin Porter). Very soon, Bhatwadekar was joined by other names like Narayan G Devare, the Patnakar brothers and Hiralal Sen, who made factual films that documented day-to-day life in India. A company dedicated to filming newsreels, the Calcutta Film Gazette, was also started during this period.

Despite these facts, the credit for making the first Indian film has always gone to Dundiraj Govind Phalke, partly because none of the films before Raja Harishchandra have survived and also because of the fact that the documentary, or non-fiction film has never been taken seriously in India. But such a claim would be tantamount to assuming that the father of film would be George Melies and not the Lumiere Brothers or Edison.

What makes this celebration even more interesting is the fact that most histories of Indian cinema do recognise the earlier pioneers but since Harishchandra was the first full length motion picture made entirely by an Indian crew, at a full six reels (of which only two have survived) the film and its maker have been accorded first Indian film and first Indian filmmaker respectively. Nowhere do you find a voice that challenges this assumption.

Well, yes, there has been a challenge to this assumption, but of a wholly different kind. The argument that generally goes around is that it is not with Phalke's Harishchandra, but with Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali that Indian cinema really begins. Mrinal Sen has been the most vocal about this stance. Though there is no doubting the greatness of Pather Panchali and the fact that it paved the path for a more personal cinema in India, such a claim only amounts to elitism. Yet it could generally be accepted that few filmmakers in India before Ray approached cinema in a wholly original way without the trappings of the theatre or literature. But it does not call for overlooking the achievements of the earlier filmmakers.

So will this piece initiate any debates on the real beginnings of Indian cinema? Very unlikely. Meanwhile, the celebration of our cinema's hundredth anniversary will be celebrated with full pomp and the glorious "achievements" of mostly Bollywood cinema will be glorified as part of the celebrations.

Directed by Ben Affleck

Written by Chris Terio

Starring Ben Affleck, Bryan Cranston, John Goodman, Alan Arkin

The moment I heard about the movie and its plot, I had a slight suspicion about what I thought the movie would be about. When the film won the Oscar for the best motion picture (announced by the first lady Michelle Obama at that), my suspicions were almost confirmed, and when I caught the movie at a local theater, I was convinced not only that I was right, but also the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences recognises films that seek to establish the political superiority of the USA, or "whites" in general.

How else would you describe an Oscar winning film that is so conventional that it is hardly distinguishable from a normal Hollywood release? Every dramatic device in the film has been incorporated at the most predictable moments, and there is hardly any mark of individuality to been in the movie, which can be seen from its visual and sound design. The tight camerawork, rapid cutting combined with the occasional one-liner makes for a tedious movie experience.

The film actually is inspired by true events, when the American embassy in Tehran was boycotted by Iranian revolutionaries during the Iranian hostage crisis of the late 1970s, and around 50 Americans were taken hostage, of which six escape into the Canadian Embassy. To rescue the six Americans, CIA exfiltration specialist Tony Mendez (Affleck) hatches up a plot where he travels to Iran as producer of a fake movie "Argo" to scout locations for the film. He travels to the country not only with false documents about a movie that is never going to be made but also with false identities for the six Americans who are currently in hiding.

The propaganda in the film is so blatant in its portrayal of Iranians as people driven wild by fanaticism, who try to resist violently the "sophistication" that America has to bring to them (as if the lynching of blacks in their own country were not driven by fanaticism). So as to prove that its claims are true, documentary footage of the time is interspersed in between the film.

Like Danny Boyle's Slumdog Millionaire, another Oscar winner from 2008 (for the same reasons), Argo is essentially about proving why the third world deserves to be the third world and why the whites will always be superior. By giving it the best film prize, the Academy recognised it not for its artistic merit but for reinforcing the idea that the USA would remain leader of the world.

Written and Directed by G Aravindan

Cinematography Sunny Joseph

Editing KR Bose

Music Salil Choudhary

Starring Mohanlal, Neena Gupta, Neelanjan Mitra, Shobhana, Padmini

Vasthuhara or The Dispossessed, Aravindan's final film, takes up a theme that is of historical significance. But instead of treating it in its broader context, Aravindan pares it down to the personal, which in turn reflects the larger society around it. Aravindan's cinematic swansong is a portrait of a people who have been deprived not only of their land and wealth, but their very identities, making them refugees in their very own land.

The film opens with newsreel footage of scores of people migrating from East to West Bengal during the post-independence partition, as a voiceover describes the suffering the migrants are put through. From there, we cut to 1971 in Calcutta and are introduced to Venu (Mohanlal), a Malayalee officer at the Rehabilitation Ministry who is involved in relocating refugees based in Calcutta to the Andaman islands.

One day he is approached by Arathi (Neelanjan Mitra), a middle-aged Bengali woman who requests him to deport her to the islands so that she and her two grown-up children can escape from their impoverished lives in Calcutta. The woman comes across Venu as being familiar, be he is unable to figure out how. Further probing reveals disturbing truths about Arathi's connection with Venu's family, and her daughter Damayanti's (Neena Gupta) dislike for Malayalees. We do not see much of her son, except in the scene when Damayanthi takes her to him, who is under hiding due to his involvement in the Naxalite movement.

Aravindan being a high-brow intellectual himself, is apparently disdainful of the pretensions of the Malayalee, as is evident in the scene where a group of Malayalees in Calcutta discuss the greats of Bengal literature surrounded by food and drinks but are apparently oblivious to the harsh reality that surrounds them. Often, the greed of the upper classes in Kerala when it comes to property is highlighted in this film rather explicitly, which is unusual for an Aravindan film.

Based on a novel of the same name by CV Sreeraman, The Dispossessed is deeply humane in its regard for the woes of the expatriates, though Aravindan is never vocal about his empathy. He prefers to give us small visual cues from which we have to relate to the whole.

Like in his other work, The Dispossessed takes on a loose narrative structure, taking occasional detours by focusing on the faces of refugees as they are being transported to the islands, intercut with images of a Durga Puja, one of the most important festivals in Bengal, and the immersion of the Durga idol in the Ganges. The film ends with the refugees being transported in a ship, followed by newsreel footage of the exodus of 1971 and the India-Pakistan war that eventually culminated in the creation of Bangladesh after another round of horrible bloodshed. The downtrodden of the earth are indeed a condemned lot.

Written & Directed by Kamal

Starring Prithviraj, Mamta Mohandas, Chandni, Sreenivasan

Cinematography Venu

I have a hunch that more than telling the story about a long-forgotten pioneer in Malayalam cinema, director Kamal (not to be confused with actor-director Kamal Haasan) wanted to take his viewers through a journey to the times when films where made on film and projected through film. Though 35mm screenings have remained the norm until a few years back(I'm talking about India), the movie going public were largely ignorant of how a series of 24 still pictures flickered on the silver screen to create movement ever since they were bombarded with several video formats like the VHS, VCD, DVD and now the Blu-Ray. Nostalgic crap, you would say, but it is also evident of the attachment an artist can have with his tools.

This feeling for a fast-dying tradition is evoked throughout the movie, right from the first scene when a child burns an entire reel of film down to the last scene, where JC Daniel's last son, Harris (Prithviraj again) confesses that he had burned the only copy of Vigathakumaran (The Lost Child), the first film made in Kerala, by a Keralite. Several such glimpses abound in the movie, like in the scene where he holds out a strip of film to his wife Janette (Mamta Mohandas) and explains how the illusion of movement is created. Another moment is while he lovingly rewinds a reel of Chaplin's The Kid and briefly dwells on Chaplin's image embedded on each frame.

One of the disappointments I encountered with Paresh Mokashi's Harishchandrachi Factory, which documented the making of the first Indian film Raja Harishchandra, was that despite the better quality in the acting, the filmmaker hardly touched upon this aspect, and worse, treated silent films as an anachronism. Celluloid, on the other hand, dwells on its protagonist JC Daniel's (Prithviraj) initial fascination with the film medium and is more respectful of the early films, as seen when the local townspeople witness a screening of The Kid which is held in high regard by our protagonist. If the film is to be believed, JC Daniel had set his ambitions higher, and unlike the staple mythological films made in the country at the time, wanted to make a "social drama" that could stand on a par with Chaplin's masterpiece.

The first half of the films are laden with a lot of humour, when Mr Daniel begins shooting his film and has to handle actors who have never seen a motion picture camera before. The social context of the times is also an important sub-plot in the film, especially the despicable tradition of caste oppression, which Daniel boldly defies by roping in a lower-caste woman Rosamma (Chandni) for the role of a Nair woman in his film. This will turn out to be the nemesis for Vigathakumaran, the film whose fate turns out to be exactly that of its title.

The film's second half chronicles how Chelangatt Gopalakrishnan (Sreenivasan), the writer, catches up with an aged, impoverished and forgotten Daniel and writes his biography, the only source of reference for anything related to the pioneer, and we follow his struggles as he tries to get the government to give the forgotten pioneer credit as the father of Malayalam Cinema. Though not as interesting as the first half, it still is an interesting watch, thanks to a decent script by its director Kamal.

I would, however, not call the film a masterpiece, especially not when you have Prithviraj, the lead actor, delivering an uninspired performance, which is the same of all his films. But you take it for granted that there are no other actors in the industry young enough and can get the Travancore accent right, besides the fact that you need a familiar face to bring the audience to the theatres. Equally unimpressive is Mamta Mohandas' performance, though she does better in the second half as the aged wife. This handicap of the film is given redemption by a strong supporting cast and by some impressive production design.

Despite its flaws, Celluloid is still a recommended watch since it is, to me, more original than what normally passes for as "new generation" cinema in Kerala and the downplaying of musical numbers as seen in a handful of recent releases is indicative of a sort of recovery in Malayalam cinema, which, for more than a decade, was hell bent on churning out stuff that looked like its counterparts in Tamil and Hindi.

.JPG/585px-Raja_Harischandra_(1913_film).JPG)