Directed by Mani Ratnam

Written by Mani Ratnam, Suhasini

Cinematography Santosh Sivan

Starring Mohanlal, Prakash Raj, Aishwarya Rai

Mani Ratnam called Iruvar- the original title of the film- his best work (so far). As far his other films go, I remember watching only Nayakan, Anjali and Mouna Ragam, and my memory of these films are too distant to make any remark on them, having seen them at a time when I had not yet donned the 'cinephile' mantle. But I would not hesitate to call it one of his best, in spite of its shortcomings.

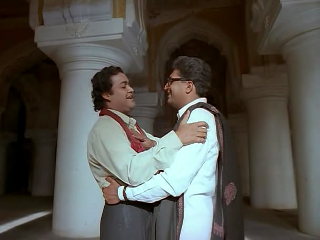

Set in Tamil Nadu in pre-independence India, The Duo charts the lives of the actor Anandan (Mohanlal) and the writer-cum-politician Tamilselvam (Prakash Raj) over a period of four decades. The two meet as ambitious young men who want to make it big in the world. Both become successful in their respective fields, each using the other for boosting mass appeal. But with time they become increasingly distant, giving way to jealousy, which is then transformed into political rivalry when Anandan makes his foray into politics, usurping his once-close friend as Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu. The film then concludes with Anandan's death while in office, and that is when the bond between the two protagonists is eventually reconciled. A major sub-plot of the film involves the private lives of the two friends, and how they shape the development of the protagonists' lives, and subsequently, the narrative.

As is very well known, the film is a slightly fictionalised account of the relationship between the legendary MG Ramachandran ('MGR' as he is popularly known) and DMK chief M Karunanidhi and attempts to examine the eerie relationship between cinema and politics in South India, especially Tamil Nadu. The narrative progresses in episodic fashion as it shifts between the lives of each of the protagonists as they move through each phase of their lives.

Unfortunately though, what was intended to be a fictional account of two of the most influential lives in the recent history of Tamil Nadu ends up looking something like a fictional biography of the actor Anandan, thanks to six song sequences devoted exclusively to him and a more-than-cursory emphasis on his private life, largely to boost the career of then débutante Aishwarya Rai. As director Ratnam himself admitted in the recent book Conversations with Mani Ratnam, a selection of interviews with critic Baradwaj Rangan, the fact that the film was set largely in tinsel town gave him an excuse to include a number of song sequences that, while being placed in films within the film, also underlines the development of events in the star's personal life, besides drawing the crowds to the cinemas (the film failed there, however).

While the idea is no doubt commendable, six songs put together constitutes significant screen time which could very well have been devoted to the film's core concern, which is all but overshadowed. As a result, the film not only loses its equilibrium but also risks seeming obscure to an outsider, who is likely to question the plausibility of a screen idol suddenly becoming Chief Minister of a state.

And yet, The Duo remains a remarkable movie for a number of reasons- a screenplay that contains several scenes of inspired brilliance, backed by equally inspired lead performances from Mohanlal and Prakash Raj. Mohanlal is especially memorable in this film, delivering probably one of the five best performances of his career. Undoubtedly, the effortless ease and spontaneity with which he is able to articulate otherwise complex states of mind purely through facial and bodily expression instead of dialogue, is some achievement, and something that is sorely missing from his work of the past decade and a half. And when I say that I decided to watch this film solely to watch his performance, I am not exaggerating.

Mani Ratnam's mise-en-scene here also deserves mention. As he revealed in the book, he sought a rapid departure in style, minimising editing and covering sequences in single takes in several instances. And this he seems to have pulled of remarkably; some of the film's sequence shots seem to be straight out of Mizoguchi (I'm not sure, however, if Ratnam was consciously emulating the great master). As always, he makes the best use of available lighting to create visuals which, while being beautiful in their own right, do not become obtrusive.

With all its virtues, a little more attention to the narrative could have made the film a genuine masterpiece. But Mani Ratnam still cannot shake himself of some of the banal conventions of our commercial cinema. He still had to have that scene where the hero waits until the train moves to say goodbye to his beloved wife.

My stint at this year's edition of the

International Film Festival of Kerala happened to be shorter than

last year's, lasting hardly two days. So, I could watch no

more than five films, and none of them were in the competition

section. Nevertheless I am going to chart down what I thought of the

films I saw below, since I don't want to keep my readers waiting for

my next entry (what pomposity!).

At least, I was lucky enough to watch ATouch of Sin, one of the year's

most acclaimed films by the Chinese Jia Zhang-ke. Far from the rosy

portrayal of contemporary China that we are used to hearing in the media, the film is built together out of four separate stories,

none of which have separate titles or common characters but a common

theme: helpless individuals caught in an increasingly corrupt,

materialist and profit-driven world, driven to commit acts of

violence, against others and oneself. The pace of the film is, for

the large part, contemplative in tempo, with sudden outbursts of

violence. Cinematographer Pawel Edelman captures the Chinese

landscape in all its serenity, starkly contrasting it with the bleak lives of the

characters in the four stories.

Later,

I caught up with Claire Denis' 2001 film Trouble Every Day,

a multilingual erotic horror film that is centred on two parallel

stories, one of an American couple and the other of a French couple,

both in Paris. While the American husband is impotent, the French

wife's sexual appetite is so insatiable that she engages in sexual

encounters with various men, and ends up drinking their very

blood. That is all the plot there is to this film.

In what seems to

me to be a surreal exploration of the discrepancies between male and

female sexuality, Trouble Every Day has

more than its fair share of gore, including an extended lovemaking

scene that ends in cannibalism.

The Mozambican film Virgin Margarida by Licinio Azevedo charts the experiences of sex workers in guerrilla camps in post-colonial Mozambique in the 1970s, into which a teenager Margarida (Iva Mugalela), mistaken for one them, is forcibly deported. Under the leadership of a woman guerrilla who is single-minded in her devotion to 'cleanse' them of their colonial mindset and make 'new women' out of them, the women, along with Margarida, undergo harsh training sessions with harsh punishments for dissenters.

While director Azevedo definitely has got his heart in the right place in wanting to show how the revolution could bring about little change in the lives of ordinary citizens of the country and his script mixes irony and drama with relative ease, his performers, however, are unimpressive, chiefly because they fail to make the transition from the comic to the dramatic in their performance. But there is no denying that the film feels quite like one of our day and time, not of a distant period.

Perhaps the best film I got to see at this festival was The Crucified Lovers (1954), one of Kenji Mizoguchi's late masterpieces, in a 35mm print that had good contrast, despite the infrequent scratches. I had never seen Mizoguchi on the big screen, so I did not let go of the opportunity. As always, his indictment of Japanese patriarchy and hypocrisy is at his scathing best in this tale of a samurai's wife who is accused of adultery with one of her manservants, while her husband himself has a sexual interest in her maid.

Like his other masterpieces, The Crucified Lovers is testimony to Mizoguchi's genius as a visual stylist, especially in his trademark long takes, letting the action unfold in distanced views using a moving camera. Watching it on the big screen, I was once again convinced that he is, no doubt, one of the great masters of world cinema.

My last film at the festival, Act Zero by Gautam Ghose was the only Indian film I could see on this trip, one that tries to encapsulate in two hours and ten acts the various issues that haunt the country. While the basic premise is that of the CEO of a Multinational trying to invade the lands of tribals by deporting them and mining the area for bauxite, resulting in tensions between the tribal community and the CEO, the director crams in issues like Maoist insurgency, communalism, and throws in a fictional Binayak Sen. The result is an ineptly shot, preachy and didactic film, but one that is nevertheless watchable, thanks largely to the performances of Konkona Sen Sharma and Soumitra Chatterjee.

Thus ended my all-too-brief stay at the festival. There were several other films which I would want to have seen, especially the Jean Renoir retrospective, which screened such titles as Toni and La Bete Humaine, and a special section on German Expressionist cinema, which included such 20s classics as The Cabinet of Dr.Caligari and A Throw of Dice, which is set in India. But there's always another chance.

Written and directed by Aki Kaurismaki

Cinematography Timo Salminen

Starring Andre Wilms, Kati Outinen, Jean Pere Daroussin, Blondin Miguel and Pierre Etaix

It is not very often that a film labelled "art house" features a happy ending and gets away with it. But (Spoiler Alert!) Aki Kaurismaki attempts exactly that in this comic drama set in the French coastal town from which the film derives its title. And the way the film has been received at major festivals, it could very well seem that the director's courage has paid off.

Centred on an aging shoeshiner Marcel Marx (Andre Wilms) and his efforts to protect and rescue a young African stowaway Idrissa (Blondin Miguel) by dispatching him off to his mother in London, Le Havre could, in lesser hands, turn into an escape thriller in the Hollywood tradition. But Kaurismaki has the entire action played in deadpan, infusing the film with a sense of detachment that only adds to its charm. Yet the film does not fail in winning our empathy for Marcel, Idrissa and Marcel's ailing wife Arletty (Kati Outinen) hospitalised early on in the film with an illness for which the doctor (Pierre Etaix) says there is little hope.

Marcel's efforts at sending Idrissa to London puts him at odds with inspector Monet (Jean Pere Daroussin), whose efforts he must evade to accomplish the task he has set out for. An even greater challenge is raising the money for the journey. But Marcel is determined in his resolve to help the boy.

The thing that is striking about Le Havre is its imagery. In both the photography and the mise-en-scene, Kaurismaki's style is deliberately old-fashioned. Not only is the staging resourcefully simple, with minimal camera movement, but the film, so it seems to me, has completely stayed clear of any digital manipulation, completely keeping its faith in the photo-chemical process. That takes some courage, especially these days.

Watching the film, one is initially confused as to the period in which it is set. While the initial scenes, with Rock 'n Roll music in the background may have you believe that the film is set somewhere in the 70s, a reference to the Al-Qaeda would confirm that the film is set somewhere in the post 9/11 world. Though the film does not make any explicit political statement, it is hard to miss the political undercurrent that runs through it.

Le Havre, in that sense, is Kaurismaki's way of keeping faith in humanity even in our deeply cynical times, that there is room for compassion even in turbulent times. To condense the review in a nutshell, Le Havre brings together the humanism and politics of Chaplin and the deadpan humour of Keaton.

Written and Directed by Satyajit Ray

Based on the novel "Pather Panchali" by Bibhutibhushan Banerjee

Cinematography Subrata Mitra

Starring Kanu Banerjee, Karuna Banerjee, Subir Banerjee, Uma Dasgupta and Chunibala Devi

I first saw Pather Panchali at a film society screening, when I was still in college and had little exposure to what cinephiles term "world cinema". My first experience of the film left me confused, to be frank. While the film's beautiful images and music no doubt caught me unawares, I was definitely in the dark as to what the film was coming to say.

I definitely understood that the film was centered on a poor Brahmin family living under grinding poverty in rural Bengal, but all I could see was a series of incidents centered around them, with hardly a plot, and it moved at an excruciatingly slow pace. Where lay the greatness of Pather Panchali? Does it lie hidden in some obscure symbolism, or is the film and its adherents merely being pretentious?

Over the years since then, I happened to see the film close to 10 times in its entirety, and went through every possible literature on the film that I could lay my hands on. Slowly, the film grew on me and I began to realise that the film had no hidden meaning, that everything the director wanted to convey is all there for you to see and hear. Even the novel on which the film is based- and which I haven't read -seemed to contend itself simply with acquainting the reader with the rhythm of life in rural India, it is said.

Soon, I learnt that a story need not always have a plot as in conventional dramaturgy, that it could take the form of poetry as well, by emphasising mood, atmosphere and character psychology instead of plot points. Taken that into view, Pather Panchali does qualify as a masterful piece of filmmaking.

If I failed to "get" the film, as many members of the audience felt during that first screening, it had to do with conventional notions of what comprised "good" or "meaningful" cinema; one of the prerequisites was that you had to have a plot-driven storyline, preferably one with a "message", some hard hitting dialogues, and a style intent on realism. Barring the last of the criteria, Pather Panchali meets none of these.

While the film has often been brushed aside as dry staple for intellectuals to feed on, Pather Panchali actually is a film that needs to be savoured with both the head and heart, only that you needed a heart of a different kind. While you used your brain to admire the way Ray has transformed words on page to an audio-visual experience onscreen, you needed a heart to take delight in such sequences as the one in which young Durga and Apu follow a sweetmeat seller, their astonishment at catching their first glimpse of a moving train, the way villagers react to a band's rendition of Tipperary, and the moments depicting the onset of the monsoon.

While Satyajit Ray's debut feature enjoyed tremendous critical and commercial success around the world, playing in over 20 festivals, it was not without its share of detractors, many of whose claims seem downright ludicrous. While the film received a lot of flak back home (with former Indian actress and Member of Parliament Nargis Dutt leading the tirade) for not showing India as a prosperous country rife with beautiful men and women singing and dancing their way through life, the western world was fairly appalled with its depiction of poverty, and a leading critic for the New York Times lampooned the film's loose structure in his review, saying the film would hardly have passed for a "rough cut" in Hollywood.

Ray, however, was humble enough to acknowledge the last of these claims, for the opening scenes of Pather Panchali are not very promising. Since every member of the crew were amateurs, the film, shot in sequence, bore the marks of a novice in its opening sequences. You felt instinctively that the camera positions were inadequate in some shots, that there was no clear spatial orientation, and cuts were often made at the wrong moments. But as the film progressed, you could clearly sense that this the work of an artist who has a grasp on the aesthetics of the film medium.

While Pather Panchali is by no means Ray's best work, it is definitely the film for which he is most remembered, for the impact it created in international film circles and for the fact that it heralded the arrival of a great master in the scene, the availability of whose films are increasingly becoming unavailable in the country of his birth except in badly damaged prints and DVD transfers.

Directed by Jean Renoir

Written by Jean Renoir and Charles Spaak

Starring Jean Gabin, Marcel Dalio, Pierre Fresnay and Erich von Stroheim

With Grand Illusion (La Grande Illusion in French), the international film scene had taken notice of a hitherto unknown film-making talent- Jean Renoir, son of the famous impressionist painter Pierre-August Renoir. Renoir had been making silent movies from the 1920s and tasted success in the early 30s. With Grand Illusion, he became an international celebrity and the film was a popular success worldwide. Released in 1937, two years before the outbreak of WWII, the film's anti-war stance made it all the more significant.

But Grand Illusion is not set in the trenches. The film begins with the French Lieutenant Marechal (Jean Gabin) who, along with Captain de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) are captured by the German forces in an air raid during World War One and shuttled between prisoner-of-war camps in between their efforts to escape. In between this cat-and-mouse game, we come across a range of characters like the Jewish merchant Rosenthal (Marcel Dalio) and the German aristocrat Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim), bonds are formed across religious and national borders, and hope is revived in the human spirit.

While the term "war film" generally brings to mind a film with loads of violence, action-packed sequences and a somber ambience, Renoir's war film replaces them with warm humour and compassion, that most essential of human qualities.

Two decades before Grand Illusion, Chaplin's Shoulder Arms (1918) dealt with life in the trenches during WWI, where he discarded his usual sentimental approach to present us with a darkly comic view of the war. But Renoir, having been in the war himself, knew all too well that humanity could exist even in the direst of situations, even across hostile countries, races and religions. This is exemplified in the close friendship that develops between Boeldieu and Rauffenstein, Marechal and Rosenthal, and in the way the escaped prisoners are tended to by a German widow.

Accustomed as we are to reports of prisoners undergoing brutal torture in war camps, the treatment of prisoners-of-war in Grand Illusion does strike us as something new. Not only are they treated more like human beings, you also get to see soldiers having a nice time off the battlefield. Whether this was a luxury offered only the "whites", I'm not sure of.

All that aside, Grand Illusion is one of those films that has everything going for it; a well-knit script with deft characterisation, a magnificent ensemble cast, beautiful background score and Jean Renoir, what more could you ask for?

One of the aspects of the film that remains striking today but was overlooked at the time is Renoir's mise-en-scene. In the first decade of the sound film, when cameras equipped for sync-sound recording were fairly bulky, and without the luxury of shooting in studios, Renoir manages to accomplish complex camera movements which, with their fluidity, remain baffling. But at a time when Soviet montage was hailed as the pinnacle of the art of cinema, the long takes of Renoir, Mizoguchi and Ophuls was underestimated. It was not until Citizen Kane and Andre Bazin's ruminations that the long take came into vogue.

I've seen very few of Renoir's work, but of the ones I've seen, Grand Illusion takes him closest to his idol Chaplin, in its seamless interweaving of humour and pathos, and in the faith it retains in the human spirit.

Written and Directed by Charles Chaplin

Music by Charles Chaplin

Cinematography Roland Totheroh

Starring Charles Chaplin and Paulette Goddard

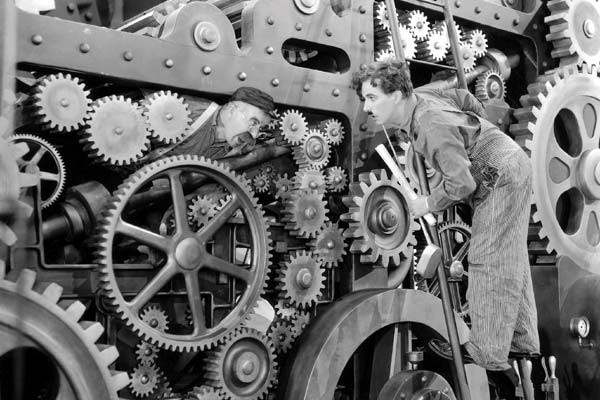

Charlie Chaplin's depression-era masterpiece Modern Times was to represent a significant change in the icon's body of work from this point on. Not only was it his last silent picture (not entirely silent, though, for reasons which we will come to later) and the last vehicle for his character of the Tramp (though a variation of the character could be seen in The Great Dictator), but every subsequent film of his- with the possible exception of Limelight -would have overt political backdrops.

With his overnight rise to international stardom in the late 1910s and subsequent entry into artistic and political circles, Chaplin began to become increasingly politically aware, and it was inevitable that his "political awakening" would be reflected in his work. His interest in world events led the actor-filmmaker to seek meetings with Mahatma Gandhi and Winston Churchill among many others. Gandhi and his views on industrialisation especially seemed to have made a strong impression on him. But it was not simply the perils of industrialised labour that the film would come to address. The devastation caused by the Great Depression of the 30s, which he witnessed on his trip and back in America, would also find their way into the film.

Despite its grim premise, Modern Times is actually a light-hearted take on the social realities of the time. While general reviews of the time could see nothing beyond the humour, other critics were miffed with the film's refusal to talk when the world was held in sway by talking pictures, its eschewing of plot, and its simple visual style, which seemed dated to many. More highbrow critics disdained its political ambiguity.

There is no doubt that the film does veer in tone- the futuristic vision in the initial factory sequences giving way to a more contemporary milieu in the rest of the film, Modern Times is rather uneven in tone. But the brilliance of these sequences more than compensates for this minor flaw.

The opening montage- A shot of a herd of sheep dissolving into one of factory workers and a shot of a large factory, is very evident of Chaplin's political leanings. What follows is a series of sketches that begin with the Tramp tightening nuts in a factory that manufactures God-knows-what, until he himself goes nuts over the increasing demands thrust upon him and other workers. Joined by a gamine (Paulette Goddard, his third wife), they fight it out against a world that is becoming increasingly mechanised and profit-driven, to assert their individuality. While they find little success, they are determined to keep fighting.

As with most of Chaplin's work, the things that stick to your mind are the set-pieces- the Tramp being used as guinea pig on a feeding machine that feeds the workers while at work so that the lunch hour could be eliminated, the home that the Tramp and Gamine dream up for themselves, the ballet on roller skates, the Tramp's routines as waiter and so on. While most of the gags aren't fresh in themselves (He does refine some of his old routines from the shorts made for Mutual two decades earlier), he improves upon them, incorporating his own physical dexterity and improved sense of timing, that they blend seamlessly into the narrative.

The characterisation in Modern Times is worth a mention. Apart from the tramp and the gamine, very few characters have any significant screen time. Even the credits mention only two characters, that of the Tramp and the Gamine, the others simply mentioned as supporting players. Their significance is reduced to that of any other prop, simply entering and leaving after their role in the story is finished. Could this be a hint that the world is increasingly peopled by automatons?

While the opening montage was enough to brand Chaplin as a leftist in an America that treats any leftwing tendency with utmost derision, another sequence that makes a more explicit reference to communist paranoia in the States would forever brand him as a Red in the eyes of Americans. This, perhaps one of the most brilliantly executed set pieces in the film, shows Charlie picking up a red flag dropped from a truck and walking towards it, only to be nabbed by the police who suspect him to be a communist leader. Using no words, and in no more than five shots, Chaplin succeeds in driving home the message. Watching this sequence, one wonders what the pundits who brushed aside Chaplin as "uncinematic", were actually thinking of.

Another remarkable facet of the film is its sophisticated use of sound. True, Chaplin was averse to talk, but he was not averse to the possibilities that sound offered the filmmaker. In his previous release, City Lights, he took the plunge into the sound film by composing a score and adding a few sound effects. But he took his experiments even further here. The only "sounds" you hear in Modern Times are the sounds of machines, of objects. The human voice is otherwise silenced, heard only through a machine like a television screen, radio, or a record. The only person who finds his voice in the film is the Tramp, who breaks into song towards the end, but which is of no particular language, for he is bereft of linguistic barriers. One particular sequence, involving the Tramp and a woman having a cup of tea, is particularly notable, anticipating the work of Jacques Tati.

Modern Times would find more acceptance in the post-WW2 era, and its influence could be seen in works like George Orwell's 1984, with its Big Brother and telescreen clearly reminding us of Chaplin's film. While the film could be considered Chaplin's most formally inventive work, it endures because of the way it resonates with our own times.

Directed by Vittorio De Sica

Written By Cesare Zavattini

Cinematography Carlo Montuori

Edited by Eraldo Da Roma

Music by Alessandro Ciccognini

Starring Lamberto Maggiorani and Enzo Staiola

Bicycle Thieves has become so iconic a film that it its reputation soars far higher than any other film made during what generally is called the "Italian Neo-realist" film movement. The neo-realist movement, which lasted roughly from the mid 40s to the early 50s, was a direct response to the devastation caused by World War II in Italy. The movement, which roughly began with Rossellini's Rome, Open City, is generally considered to have reached its artistic zenith with De Sica's 1948 masterpiece.

While umpteen films were made under the tag "neo-realist", only a handful of films have the worldwide acclaim as of now, and of the few that have, De Sica's film remains the most cherished by audiences. One could attribute this to the film's universality. While Rossellini's war trilogy was essentially Euro-centric, Bicycle Thieves, with its searingly simple premise of a man in search of his lost bicycle, made for a theme which anyone anywhere could relate to.

Like most art movements, what made neo-realism a landmark movement in the history of cinema was the distinctive aesthetic it introduced. No longer able to afford shooting within the confines of a studio or with bankable stars, filmmakers had to take their cameras out into the streets, filming with whatever light was available, and by using non-professional actors without make-up. As a result, cinema finally seemed to be shorn of all artifice, and viewers were confronted with bare reality presented to them, without the interference of any manipulation by the studio system.

There were films before the emergence of neo-realism that challenged conventional methods of filmmaking, like the Expressionist cinema of 1920s Germany, the Impressionist cinema in France of around the same period, and the Surrealist movement, but they occasionally used professional actors and studios. Films that veer close to the neo-realist aesthetic of that period would be Flaherty's Nanook of the North, which was shot on location without using professional actors, and Renoir's Toni in the 30s, which would similarly make use of non-actors. But these were individual efforts, and it hadn't yet been proved to the world that an entire cinema industry could make films that way. That would happen only after 1945. Films like Rossellini's War Trilogy and Bicycle Thieves proved that you could make a great film with only a camera and an inquisitive mind.

Yet it would be unfair to credit Bicycle Thieves as the product of one mind. For one, its plot was based loosely on a novella of the same name by Luigi Bartolini, which was turned into a screenplay by Cesare Zavattini, who wrote a great number of films during that period. Later, he would often fume at the fact that credit for the film's greatness went entirely to De Sica, and went so far as to claim that 90 percent of the film was his own creation. While you could credit the writer with his brilliant social observation in the film, since Zavattini himself claimed that he no involvement in the production, you could not overlook De Sica's contribution to the final work, especially in his mise-en-scene and the way he has evoked brilliant performances from a largely unknown cast of non-professional actors.

In its spare use of camera movements, montage and largely medium to long-shot framing, Bicycle Thieves has a stylistic austerity that is reminiscent of a Chaplin film. Even in its worldview, that of a dog-eat-dog world, it is not unlike the themes that pervade Chaplin's work. But it avoids the poetry, gracefulness, and the optimism of the Tramp, to present a more harsher, more fatalistic view of the world.

Upon release and international acclaim, Bicycle Thieves influenced several filmmaking countries of the time, notably in India, which had just emerged from colonial rule. The immediate influence of the film could be seen in films like Bimal Roy's Do Bigha Zamin and Raj Kapoor's Boot Polish, while a hitherto unknown Satyajit Ray borrowed the neo-realist aesthetic to scale poetic heights in his debut feature Pather Panchali.